Studio conversation with Andrew Kinghorn

These are garden sculptures. They’ll be on either side of a path, probably among flower beds so the plants will grow up over the base of the sculptures. Over time they’ll weather down and, as they are kept outside, they gain a patina.

The reason I like doing garden sculpture is because all the emotional drama that goes on in my heart when I’m making something is completely nullified when something goes into a garden. The animals and the birds who will use it won’t think about what it means. Theirs is a completely different relationship to the world, and I like that. My garden sculptures will take on a life of their own and I’m only just a little part of their history. A little rust will appear and they will start slowly decomposing, ivy and creepers will grow over the top, and in the future they may be abandoned completely. Once the sculptures are installed they are no longer mine, and I like just ‘letting go’ of them.

When you send your sculptures to a garden, do you come back and visit them after a while?

I have visited them out of curiosity, to see how nature affects my work. For example, the garden in Argyll is a combination of natural landscapes and a mixture of introduced plants and as the seasons change, the qualities in the garden alter completely. So it is interesting to see the sculpture in autumn, winter, spring and summer. The Argyll Garden, in particular, is visited by animals like deer, otters and pine martens and I hear all sorts of stories about these animals. I feel I know the wildlife in that garden, and I love that my sculptures are in this kind of context.

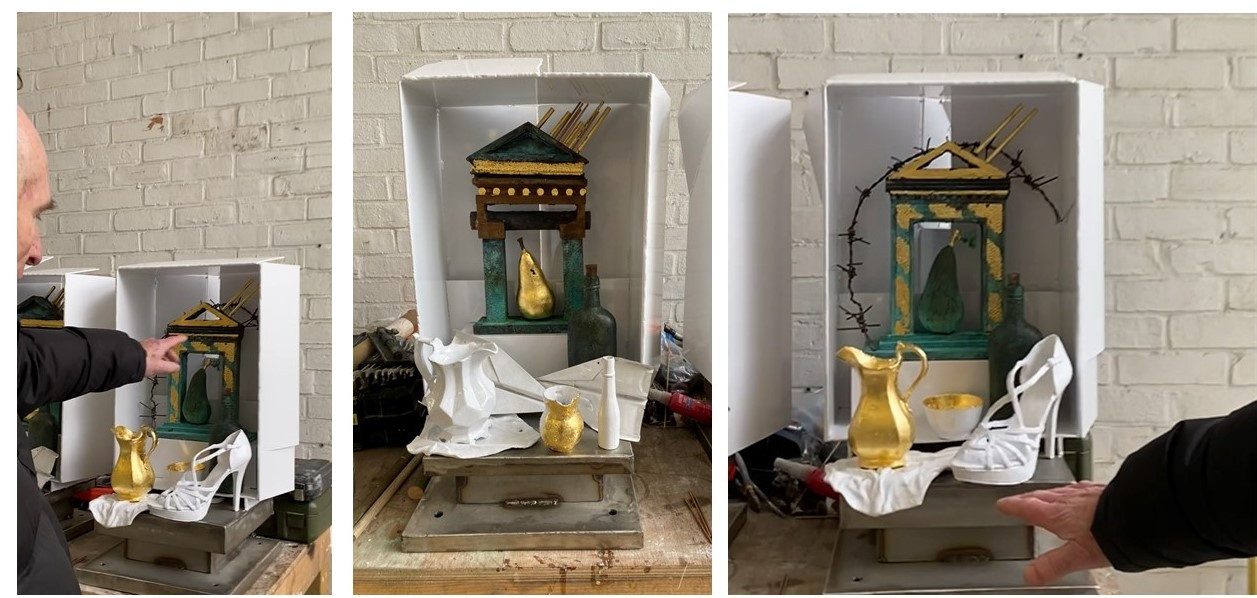

What is this other piece you are working on?

This is a wax which is going to be cast in bronze. The whole thing is a Klein Bottle. If you were a fly you could walk along the outside surface and then turn and continue to walk along the inside. It’s one continuous surface, like a Möbius strip, a Klein Bottle is the three-dimensional equivalent of a Möbius strip.

How did you manage to make the shape?

Making the shape itself is extremely difficult for something which looks so simple. I made an original wooden version of this, using a lathe for part of it. Then I had to carve other parts. Everything had to sanded down to get a perfect finish and then I cast the wax from a silicon mould of the original. I use a variety of techniques for casting. Sometimes I make a direct cast from an object, like the shoes, and other times I make a wood or a clay version initially.

I’ve just started a project about Ukraine. I saw on television two old people walking down the street, a man and a woman, not knowing whether they would both survive till they reached the end of the street. They felt that one of them could be blown up at any moment. I wanted to make a sculpture about the fragility of life, so I thought I would make pairs of things (as a metaphor for 2 people) in the shapes of bowls, and would deliberately destroy one of each pair.

I made five pairs of different bowls in bronze and my initial plan was to ask the army to use high velocity bullets to shoot them. I wondered whether they would shatter or whether the bullet would leave a hole behind as it penetrated the metal. I am starkly aware of the grim beauty of violence on shapes and materials, and in breaking things up. I would also have want to make them whole again. There’s a Japanese philosophy about imperfection (wabi sabi) and mending broken things (kintsugi). When they see things which are broken, even utilitarian plates, they’ll spend an awfully long time fixing them up. They regard the process as important. It’s rescuing it, saving the object. And they’ll use gold in a very elaborate way. The mending becomes almost a ritual.

But with these, I’ve decided that I’m not going to shoot them. It would be too violent. But I will break them in a less dramatic way. I am still considering how I will proceed.

How long does it take to finish a work?

A long time. I always have about five projects going at the same time. I move forward in a very, very slow, intuitive way. I usually don’t have a detailed idea in place before I start, just a basic, very rough concept of what I want. So, if I have five separate projects going, it means that I have plenty of time to think about what I’m doing.

As you go along in life, you inevitably pick up huge numbers of skills and techniques, and being old I know there’s always a solution somewhere. I can always think of a solution for any artistic problem, and I couldn’t do that when I was young. I didn’t have the repertoire. It’s like having a good grasp of language. When you’re young, you don’t have many words. As you get older, you get a larger and larger vocabulary.

I have a tendency as I’m getting older not to worry about trying to make money from my work; the only thing I really want is to find a good home for the sculpture I make. So I tend to give things away to people I know and who have values I admire. I have also learned from experience that making very big things generally gives sculpture a very limited life span because nobody wants them. As I get older I want to make things for smaller domestic spaces.

Covered Yard Project Space conversation between Andrew Kinghorn and Mihaela Coman on 20 February 2023

More about Andrew’s work here