Studio Conversation with ESW studio holder Hans K Clausen

For how long have you been here, in the ESW studio?

I graduated from Edinburgh College of Art in sculpture back in 2012 and myself and a colleague, Maja Quille, we received an award from ESW to have a graduate studio. I shared a studio further down the corridor with Maja for the first three years and then I applied for a studio after that.

Do you have a favorite material to work with?

I’ve often think of the magic of casting in metal, it is really lovely. I’ve cast in aluminum or bronze and I think there’s something about the fact that it has its own life, its own energy, and you never quite know how it’s going to turn out. A lot of the work that I do, especially if it’s for a commission, it has to be really well thought through and designed and it has to be delivered to a certain specification, particularly work in healthcare and hospitals, you have to meet so many regulations, fire regulations, infection control regulations… so, there’s not really much room for error or mistake. It has to be exactly how you say it will be and that can be quite constricting at times. So, when I’ve done casting, I like the idea that you give over the control to the materials and they might do what you want them to do or they might do something far more glorious than you hoped they would.

I’m also interested in the division of labour in some ways in the art world. My bread and butter job is working as an exhibitions manager for hospitals. And whenever we’re hanging exhibitions in hospitals, I’ve become aware of people’s perceptions of what makes a piece of art valuable. If there’s something that looks like it’s taken a huge amount of skill or time, for example a hyper realistic drawing or an oil painting of great detail. That instantly seems to have value or have respect, because it’s taken somebody a lot of skill and time. Something that might be extraordinarily beautiful but happened in a flash in a moment often doesn’t get perceived as having the same value. I would far rather find something, come across something by mistake or by chance that makes people stop, rather than labour away for months on end to have something that’s impressive, but it might not necessarily add anything to anybody’s day.

You are hard to impress.

I don’t know, I can get more excited about things that I find in skips than I do about things that I sometimes see on gallery walls. It’s something about that instant visual statement. It says something and you feel something in response to what you’ve seen.

Small scale or big scale?

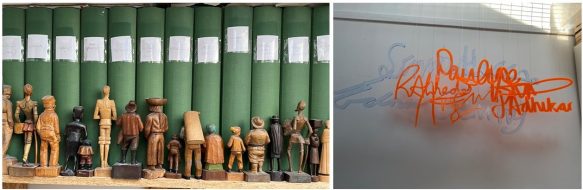

I think maybe because of my interest in collections, I often start with small objects, but then one of them or ten of them isn’t enough.

Oh, so, your word is: volume.

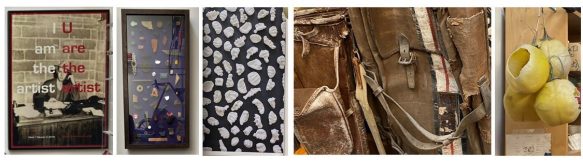

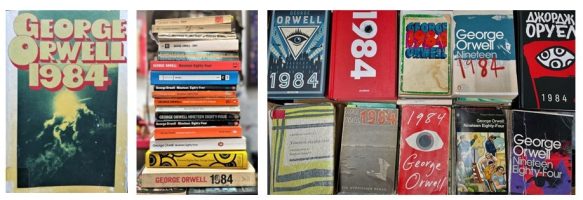

Yeah, I think that’s probably it. For the signatures sculpture commission, there’s going to be 366 of them in this cloud. One signature might look very beautiful as a single graphic, but I want it to have impact in the space, so it will be 12 meters long and five meters high. And the 1984 library installation will be almost 2,000 books, so I think volume and the significance of numbers often plays a part. Yeah, it’s not to say that bigger is always better, but I think I’m always drawn to… What can I add, when is it enough? In the past I have often made work that is site specific, that I know where it will be presented. In that case I would like the volume of the work to be appropriate to the volume of the space, and whether that’s something that sits nicely on a pedestal, and it fills the pedestal, or whether it’s something that fills a room. If I think of art that I’ve been impressed by, art that I love, it does tend to be bigger. Installation work like that by Christo and Jean Claude and Jannis Kounellis ‘s work, I’ve always loved. So, it wouldn’t be enough just to create something out of a glass bottle. It needs to be created out of 500 glass bottles or five tons of coal, or whatever it is, I want to be stopped in my tracks and often the thing that might do that for me is scale or volume and how that relates to the space that you’re in. It’s always more difficult to do that outdoors to make a really impressive piece of public art outdoors as the scale of the setting is out of control, there’s nothing to limit it.

It’s lost in space. Do you have projects you are thinking of for the future?

There’s lots of things here that I need to revisit and I think there’s always that thing about time. How you divide time between making and thinking and experimenting and then all the other stuff, the admin noise. And things like that, looking up on the corner there, there’s a bunch of plastic coconuts which I’ve brought back from Athens, they used to have light bulbs in them and they would light up, part of a plastic palm tree that was outside a car dealership, a symbol of something exotic and aspirational. It no longer lit up when the sun faded the colours and it just became like a curiosity to me. I packed them in a suitcase to bring them home and they’ve hung there for 3 years. I feel there’s something that needs to be done with them. There’s a conversation to have with them. When I look at them, it’s like we’re talking and I need to find a way of turning that conversation, that visual dialogue, into something else. Maybe casting will be a way of trying to stretch that idea. What happens if I cast these? Or what happens if I sit and draw them for a few days?

There are many things around here that are waiting for me to pick them up. The other thing is probably that notion of whether we’re making things because we have to make them, and then we look for an opportunity to exhibit them, or whether when we hear about an exhibition or a commission it becomes something that we aim for.

There’s a triptych of flags, here, in my studio, which I exhibited last year at the Scottish Society of Artist annual show, three flags that are made out of hospital garments, one’s made from surgeons, scrubs, one’s made from carers uniforms, and one’s made from patients’ robes. Along with a friend of mine, a skilled seamstress, we made these three flags and they’re statements about democratising health: one says Everyone’s a healer, one says Everyone’s a patient and one says Everyone’s a carer. One day we might be capable of caring for somebody, the next day we might require care from somebody. It’s made from reused reappropriated materials, it’s made with somebody else’s skill collaborating with me. They’ve been shown, they’ve been flown- they were flown on the flagpole at Dundee University, and they were displayed in the Royal Scottish Academy but they are again something that now sits here waiting… I’m not finished with them yet.

And there’s lots of things that I’ve made or I’m making that I’ve never quite finished. It’s not like making a sculpture a physical object or a painting, and it’s done. I put a date on it and give it a title and it goes off into the world. No, a lot of the things that I’ve made or I’m making – they’re always there, waiting…

I’m very curious about what you are going to make this year.

The project with the 1984 books is a big one, I think. The Winston Smith Library of Victory and Truth – I’m constructing a touring installation and library built around a collection of 1984 copies of Orwell’s novel, 1984. I have to build a physical structure that will house the collection of books, and these old megaphones from 1940s, and this 1930’s typewriter, and other bits of paraphernalia will be part of the structure. It is going to be an interactive installation which also serves as a meeting place and performance area. I hope to take the whole thing to Jura next year and then on a tour of the UK.

You build an entire story around an object.

For me, objects and stories are inseparable, everything has a narrative and I think my job as an artist is to find a platform, an audience, and the purpose for sharing that in an exciting and engaging way.

More about Hans’ work here