Studio conversation with Kat Cutler-Mackenzie and Ben Caro

Kat, Ben, you two share the same studio.

Yes. We started working collaboratively in 2021, the final year of our degree. We were at home together, over lockdown, and the lack of sculptural facilities prompted us to start making image-based works again.

We both did a joint degree called the MAFA at the University of Edinburgh, which covers both history of art and art practice. That greatly informed our working practice, with its emphasis on being a 50% academic and 50% practical degree. We definitely treat our practice as research. In fact, we’re particularly interested in artistic approaches to art history. Despite creative innovations in art historical research, more value is still given to written academic texts than to research sensitive to oral, felt or even smelt histories of art. It can be prejudiced towards a very particular, academic understanding of history which was established during the enlightenment, and that’s something we want to investigate.

You provoke discussions.

Yeah, I think tentatively, we never want to be too didactic about what our work does, we don’t want to go head on into the work saying ‘it’s going to make a definite change in the discipline’ because, at the moment, we’re testing things out. We’re learning what we do.

We tend to work in photography and slide projection, and slide projection has got this fantastic pedagogic history as a teaching aid in schools and universities. It works great with my background in collage because there’s lots of juxtaposition at play. We’re particularly interested in dual channel side projection, and maybe extending that in the future into multi-channel, to have even more networks of images at play in our work.

Kat, what is your background?

I’m particularly interested in collage, and the historiography of feminist theory is always at the backbone of my research. Some of my time is spent writing academic papers as well. So, I suppose that’s where I come from.

And yours, Ben?

My background comes from sculpture, but also archaeology. I studied archeology alongside my degree for a couple of years and that definitely informs my artistic practice as well. The research project that we’re both working on informs the theories that we’re thinking about, but there’s usually a feminist angle too.

Are you working now on a specific project?

We’re showing one of our slide projections at Hidden Door Festival in Edinburgh, which runs from May 31st to June 4th. The theme of the festival is environments, with, for us, a focus on the environment of the museum. The curatorial team had seen the work that we made during our graduate residency at ESW called Staging a Gaze, and one of the ideas that we were exploring was this idea of “contact zones”, the space between artefacts and viewing publics in a museum, underpinned by relations of “coercion, inequality and conflict”, in the words of anthropologist Mary Louise Pratt. This is the work that we will be reimagining for their space.

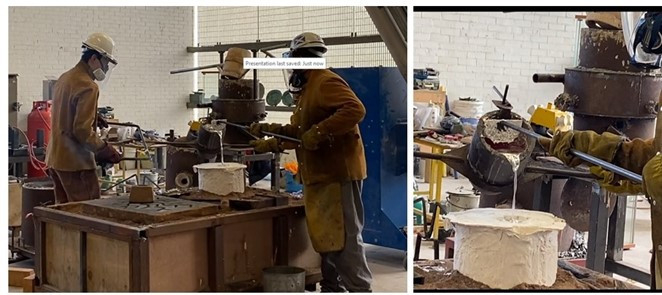

Ben, I’ve seen you casting aluminum. Was it for this exhibition?

No, that was for another work called Palimpsest, which was on display at the RSA New Contemporaries at the Royal Scottish Academy. I was exploring early cinema made around 1920 and I was using the aluminum casts to extrapolate shapes from within the images, like the nitrate star printed on the edge of the film strip, taking two-dimensional images and pulling out three-dimensional things.

Kat, your approach is quite different, how do you manage to work together?

Well, I think it’s really fascinating. We both get into a project, it often starts with an object or an historical artwork. I often start with a smell, for instance, and I think that’s where my most recent personal projects have begun. They don’t necessarily manifest themselves at the end in a scent-based work, but the olfactory history of gender often shapes the research and material that have gone into my most recent work. I think, in that sense, we both oscillate in and out of letting a material drive us and then an idea which can pull us back around again. Often our separate research projects grow branches that inform the collaborative project, and vice versa.

Is it helpful to have all those facilities around here? Do you use them?

We’ve definitely been down to the workshops quite a lot. And the space in the research room to try out stuff is super useful. In a way, it was quite diverting to jump into the graduate residency here in 2021, because we proposed to do a 35 millimeter slide projection, but arrived and just wanted to make things and learn new techniques in the workshops! So, it was great, but it was also a distraction, maybe…in a good way!

Do you have a project that you come back to thinking about over and over that you didn’t have the space or time to start on.

That’s a good question. The project we’ve been thinking about for a couple of years is called Mineral Bodies. We haven’t yet made it and it’s something we will probably take a couple more years thinking about. We are interested in silicosis and the professional illnesses that, historically, makers have developed working with materials in a workshop. The Danish visual artist and writer Amalie Smith wrote a book called Marble that has informed our thinking on and around this topic. In her book the main character is called Marble, and she is sort of a metamorphosis of coral into stone into human. We’d like to work with a community of makers to think about the experience of these illnesses, but it’s not something that we would want to just jump into or to take lightly.

In a way, you are much more interested and concerned about the process than the outcome?

I don’t know if that’s always true. I think we often see the process in the work. The process is the work, right. But we do like to get to the end of a project! I think that’s the beautiful thing about being in the sculpture workshop — you can try these little bits and you see what each part of the process looks like and what marks get left at the end of it. In my aluminum casting, for example, I was casting these small stars, but decided to leave the stars on the tree that they were cast on. It became more of an aesthetic decision, but also wanting to see the process in the world as something you can almost decipher in some way if you want to learn more about it. I think the process within archaeology that fascinates me is partly about uncovering something, excavating, we take something out of the setting that it has been in for maybe 200 years, underground, then it gets conserved, and made to be on display or to be studied.

Kat, you mentioned your disappointment in the way art history has been taught in university.

I think art history is really varied and changing, but in an academic setting we’re still very much stuck in processes driven by Research Excellence Framework. As researchers we’re often chasing the new hot idea, and we start to build up buzzwords around certain topics, et cetera. But I think the bigger interest for me, which is actually about to form the core of my PhD in September, is on how we can bring the language of performance to art history to reinvest the live body into art historical research, because I think the thing that I find most disappointing is the dry and distant way in which we’re expected to produce our work, and we still don’t treat artworks as being on the same scale or pedestal as written theoretical work. It’s almost like the artwork hasn’t been researched as well or we can’t trust it, but I think often it’s simply that we don’t know how to read it or to decipher it’s footnotes. That’s maybe the thing that sits at the heart of the struggles I have with some forms of art history. I think it’s just about expanding the types of research we do and creating disjuncts or differences in historical narration to open what Adrian Heathfield calls “dynamic[s] of creative and historical production” that maintain that the art historical narrative, or archive, is contingent and un-fixed; live; open to challenge, revision and debate.

So, Kat, you will you start your PhD in September?

Yeah, my PhD proposal has been accepted. It’s called An Artistic Turn in Art History. And it’s predicated around the idea that, as Hélène Cixous writes, ‘when words cease to breathe, the body must speak’.

Studio conversation with Graduates Studio Holders Kat Cutler-Mackenzie and Ben Caro

More about Kat’s projects and work here