Studio conversation with studio holder Benjamin Owen

Does this studio space work well for you?

I don’t know yet. I’ve only been here for two months. The people are nice and generous.

What is your story?

After University, I became a teacher immediately, teaching art in secondary schools. I was also (relatively speaking) quite politically involved with different collectives and groups. I was in punk bands, organising gigs in the Southwest and Wales, making flyers, making music, and traveling around the UK to other people’s shows. In the daytime, I was a weary schoolteacher.

I did that for 15 years and then I went back to school and did a master’s in film and photography. I am interested in the material of the photographs and affecting the surface of the photograph. I was also interested in the recording environment or social context of filmmaking and bringing my experiences as a musician and educator into that process. I got really into the idea of how the soundtrack might be made and how this affects our relationship to images, the performance, and the everyday.

So, since then I’ve combined my experiences of working with education, images, film, and sculpture. I make work through music in a lot of ways: it might be physical, it might be a film, it might be gestural and social.

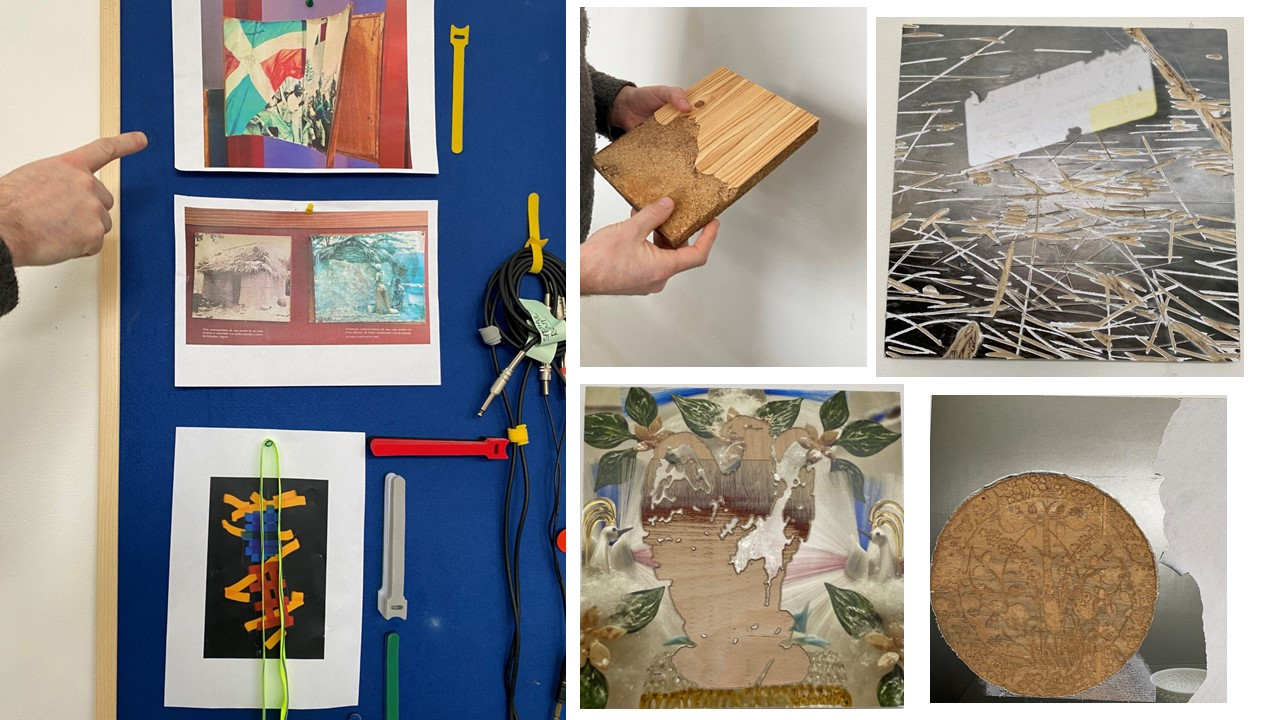

I think about music a lot because it’s emotionally immersive. I like how sensitive we are to music, but, at the same time, I’m very visually led. I’m just starting to play with these mounted images of museum objects that are record shaped. I’ve been using different methods to cut into the surface, going through the photograph into the material beneath. The cuts are figurative and usually counter to the image.

So, you are also interested in the materiality which comes with music.

Exactly!

What about your films?

My film work is all-encompassing. It’s very exhausting, but I’m addicted to it. I make films with groups of people that tend to be older than me. I lived in Bristol for a while, and I used to go and watch jazz bands in this pub, and they were generally people over 70 or 80. I found that experience and commitment very soulful. When I was younger, my mum and my gran used to do a lot with Age Concern, a charity for older people, and so it’s stuck with me. I worked with Cubitt Gallery, in London, and they did an interesting studio residency where they put artists inside empty spaces in institutions. A Dutch model, I think? I was in this care setting, with bedrooms and living rooms, a space a bit smaller than this studio. Most of the artists that did it would do the odd workshop and then just get on with their own practice.

I was interested in working with all the people there as the core of my time, and over a period of two years, we developed a sense of trust and were able to do improvised, experimental, radical work together, conversations over longer periods of time, and that’s what I wanted to do. It was great developing a connection and playing with how to spend time together. The experience of being embedded within their day-to-day was really important to me. I made a series of films where I invited musicians to improvise as part of a three-way conversational approach, and on the soundtrack level, every now and again, we would harmonies within the frame of the encounter and the film. Creating a metaphysical relationship between conversation, discord, and harmony. The multi screened work was titled Going Along Without A Body. A mixture of improvisation, conversation, time, and trust – all soulful rich things – came out of that project. I suppose I was looking for ways of pinning down elusive momentary values from those exchanges. Does that make sense?

Yeah, I’m very intrigued by this kind of work. I have the feeling that age is going to be the next major social issue. We’ll live in a world of old people.

I had a fascinating conversation with an ear-nose-and-throat surgeon, about vocal cords over time, how as we age, the drifting relationships with families, and physicality, we can sense resonance with our voice. Our body loses physical mass and bass and so our voice becomes more delicate and unsure. The psychological and physical relationship between our voice and our self-esteem is really connected. Yeah, voice health.

I’m very passionate about this way of working and this type of work. Like many others, I’ve had to get funding as it’s very self-directed work. Occasionally I get institutional support, but I don’t apply for that much. I’m passionate about the work because it riffs on education, aging, and care, and also the energy and ideas of experimental music, and film.

Within the context of new stuff, I used to be a toy sculptor, working for a company carving toys, and so I’m using hand-carving tools and some machines, to make sculptures adorned with images taken from my films.

Are you or the musicians you work with comfortably improvising?

I tend to have long conversations with them beforehand, not just parachute into a situation. It’s important they’re invested in the idea and the people to a certain level. There’s a bass player up in Dundee I’ve worked with for about five years. He’s amazing and extremely empathetic, he’s called Seth Bennett. and There’s a Japanese composer called Shiori Usui who worked with me on the last project, The New Vocal Club’ but they do their own projects as well. Shiori has been working on some beautiful sensory improvisational work with children in hydrotherapy pools.

In London, with Cubitt with the educationally led framework, I did these sessions called Saturday Socials, part of the elder program. I would invite musicians into the sessions, and we would all do painting, and listen to musical and sound abstraction. I’m very much interested in visualizing music, but I don’t tend to work with it in the sense of print or drawing, I try to capture recordings of the session sound and images of activity in a more elusive expressive way. I’ve been working with relationships between musical and sculptural grooves and vinyl dimensions and signals and acoustic baffling, which I’m obsessed with. For instance, when I showed the film ‘The New Vocal Club’ at Perth Theatre, I had the film’s audio as a visual oscillation projected on a wall. When I showed multiple films in the care setting and participants’ homes, I thought about where the speakers were in relation to people’s ears, particularly if they were in wheelchairs or sat about in armchairs. The vicinity of sound, and the presence of the portrait image exhibited in the extra care setting.

There’s a church in Corstorphine, where they’ve recovered a cinematic organ from the local cinema. The local trust raised funds to renovate and install it in a community hall. I’m fascinated with those organs, not because of the nostalgia, but because of their purpose. The idea is that it creates quite crude soundtracks, which are very sensual and soulful too. I think it’s the last one of its kind and it’s in this back room which has got all these other kinds of drum kit machines for making boat and train noises. I’ve started to make a short film about it and I’ll be working with a local primary school as a way of expanding its use and its social presence.

Talking about bringing together visuals and sound into a new phase, this carousel slide projector makes a very percussive noise, which I amplify, with these contact microphones and effects to create a very dub reggae sound. That’s a basis to improvise around a rhythm of images. A resampling in a social setting. Trying to think of more generative ways to extrapolate time and experience, rather than just letting them languish as an archive or cynical documents for funding or at best catalogues. It’s about how you can take the experience and turn it into something else afterward, a second phase.

Studio conversation with studio holder Benjamin Owen, March 2023

More about Benjamin’s work here